The Mass Observation project studied working class life in Bolton from 1937-40. Researchers under the direction of Tom Harrisson would record every aspect of day-to-day life. Here Dr Bob Snape of the University of Bolton looks at the important role wrestling played in the town’s social life

Along with speedway and greyhound racing, All-in wrestling was one of the new ‘imported’ sports of inter-war Britain that were not really new but modern developments of long-established sports.

In each case the aim was to attract paying spectators by offering an exciting and modern form of affordable entertainment. All-in wrestling originated in America and was introduced to Britain in 1930. It appealed to a mainly working-class audience and most all-in wrestlers came from a working class background.

Like many other sports, wrestling developed as a commercial proposition in the nineteenth century, initially in the form of ad hoc bouts and prize fights and later as a music hall act, where larger venues and bigger crowds made it a profitable commercial undertaking, blurring the boundary between sport and entertainment.

Unlike other sports it was not reported in newspapers which meant that it never became “big business”; it was, however, able to develop as a cult sport with a dedicated following in a period of extended economic depression and high unemployment when sport competed with the cinema as entertainment. From the outset it was subject to a critical gaze; in 1931, for example, the Times newspaper predicted, erroneously as it turned out, that British audiences would never accept its brutality and excess.

Wrestling is an ancient sport, found in Egyptian, Babylonian and Assyrian civilisations and was included in the ancient Olympic Games from 704 BC. It has historically been able to re-invent itself ever since, with early accounts of wrestling being associated with feasts and revelries in twelfth century England. In the nineteenth century the Cumberland and Westmorland Society sponsored wrestling matches in provincial areas, for example as the annual Whit Monday event in Liverpool, which drew wrestlers from Carlisle, Kendal and Maryport, and more locally from Crewe, Blackburn and Liverpool. Wrestling thus flourished in the nineteenth century as a traditional sport, loosely connected to commercial venues, regulated by rules, and providing opportunities to gamble.

The origins of All-in lie in the emergence of the Lancashire style of wrestling, likened by one commentator to a “dog-fight on the ground” and “the roughest and the most uncultivated of the three recognized English systems”, the other two being the Graeco-Roman and the Catch-as-Catch-Can styles.

By the early twentieth century the Lancashire style had evolved into the Catch-as Catch-Can style of professional wrestling in the USA.

In the absence of a national governing body, extreme violence, such as head-butting and gouging prevailed in what was sometimes little more than brawling. Somewhat ironically, in that it was almost an exclusively working-class sport, the All-in style was established in Great Britain by Sir Edward Atholl Oakley, 7th Baronet of Shrewsbury in 1930.

Contests were divided into three-minute rounds and decided on falls or a knockout. The fact that fouls included kneeing in the stomach, finger-wrenching, striking the referee and throwing the opponent out of the ring rather suggests that these were envisaged as part of the sport/entertainment.

In Tom Harrisson’s estimation, All-in was successful because it was thrilling, allowed dream-wish fulfilment and gave the feeling of being a member of a group by talking about it.

Wrestling had long been popular in Bolton as both a participation and a spectator sport; in February 1897, for example, 3,000 spectators attended the Heywood Athletic Grounds to see Joe Carrell of Hindley fight Tom Clayton (alias Bull Dog) of Farnworth in the Lancashire style for a prize of £200.

It was upon this foundation that All-in later became established in Bolton in the 1930s. Records show organised informal wrestling developing in the nineteenth century with the formation of a wrestling club under the auspices of Bolton United Harriers and Athletic Club.

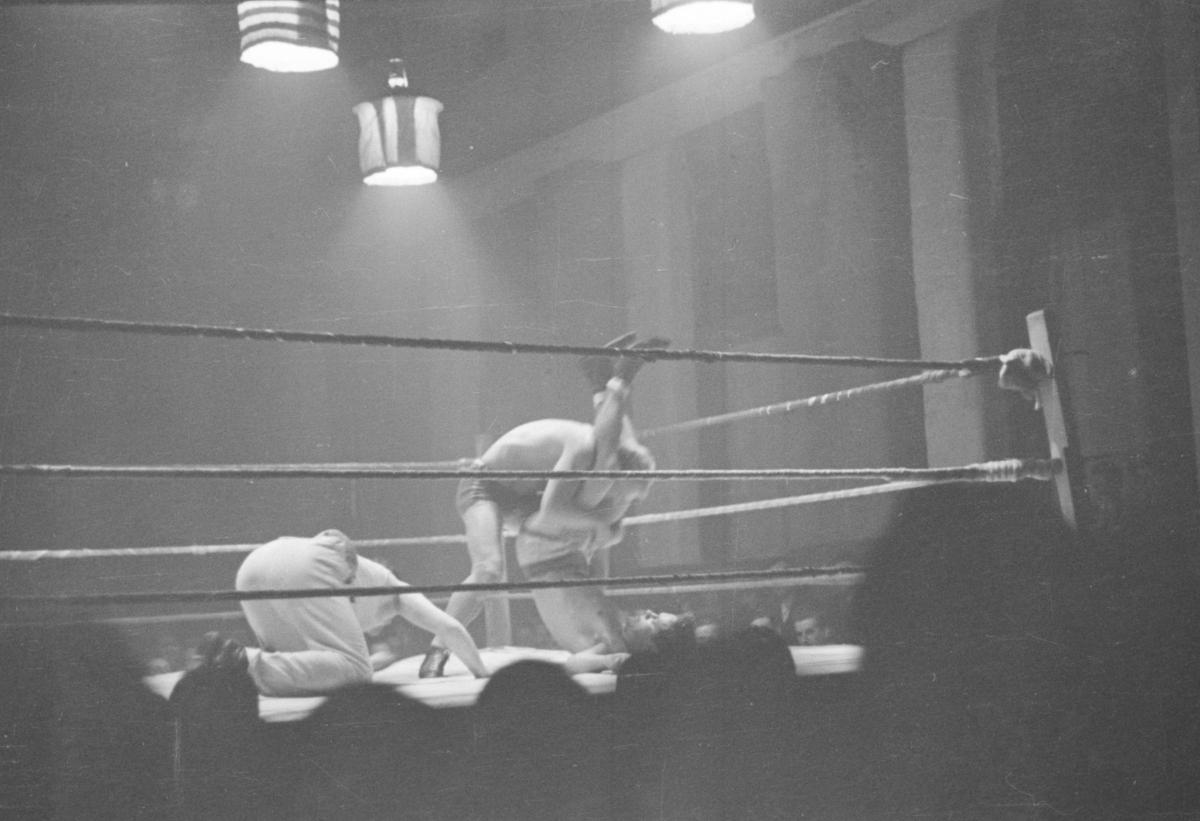

Mass Observation’s interest in All-in wrestling was aroused when Bill Naughton, a coal-wagon driver and enthusiast of wrestling who had joined the team of observers at 85 Davenport Street as a local volunteer, took Tom Harrisson to the Bolton Stadium on Turton Street, opened in 1933 as the town’s All-in wrestling venue.

The capacity of the stadium, an old building which gave an impression of “shabby elegance,” was 2,000 and it was regularly full. The crowd included both men and women, though it is worth noting that Tom Harrisson reported that women who liked All-in were seen to belong to the “lowest type”.

An All-in wrestling night at the stadium consisted of two types of fight. “Clean” wrestling, with wrestlers including Billy Riley, Lew Faulkner and George Gregory, was hard and rough with at least some respect for the rules and the referee’s decisions.

“Dirty” wrestling, on the other hand, involved significant transgressions of the rules and an overt challenge to the authority of the referee.

Promoters understood that the appeal of All-in depended upon the degree to which spectators could identify with a hero or villain.

This was encouraged through suggestively named wrestlers such as Aussie the Butcher, ‘Hard-boiled’ Herbie Rosenberg, and ‘Gentleman’ Jim. If clean wrestling was about sporting competition, dirty wrestling embodied a conflict between good and evil through role-play.

One promoter told Tom Harrisson it was not good enough for a wrestler to be clever; he had to be a good actor too. A graphic account of a match between Harry Pye (Doncaster) and Harry Brookes (London) at the Worktown Stadium, published in Britain by Mass Observation, one of the first Penguin books, provides a good example of this.

Pye rushed across to Brooke’s corner before the start of the second round, grabbed him by the hair and kneed him in stomach. As Brookes lay screaming, Pye came across, lifted him up and threw him out of the ring and then ran around beating his chest, much to the annoyance of the crowd to whom he had become the villain.

Next, as the observer, who had to dodge a piece of iron thrown towards Pye from the crowd, reported: “The din is terrific – crowd shouting ‘Dirty Rat’, swine, lousy pig, then missiles hurtle through the air – lighted cigarettes, a key, a piece of billiard chalk. Pye won’t let Brookes or Ref. get back in the ring, spectators shaking their fists at him. The hall is an uproar.

“In the next round ref attacks Pye with a stool, Pye chases Brookes, Brookes picks up water bowl and with a terrific bang lands it on Pye’s head. Brookes then gets Pye in a death-lock and Pye submits. Brookes the winner goes to shake hands with Pye who refuses and tries to hit Brookes. Brookes kicks him four times in his weakened leg. The crowd cheers. At some point a young woman shouts ‘tear his bloody arm off’.”

What did the spectators make of all this? In September 1938 Mass Observation launched a prize competition inviting people to say what they liked and didn’t like about All-in wrestling. Several respondents had never been to an All-in fight but had anyway decided on hearsay that it developed the “lower side of men’s nature” or that the matches were faked. One had been told by a friend that the spectators were mainly of the “uncouth, uneducated class who were always seeking some kind of thrill” another that it was not human or civilised.

Regular spectators expressed more positive opinions: All-in was the best entertainment in Bolton; there was no sport to beat it; it was sport, humour and thrills in one entertainment.

The crowd itself played an active part in providing entertainment; as one spectator stated: “The stadium is always crowded …then the audience start making their noise; each time I go I grow more fonder of it, and I’m sure if anyone wants a night of good entertainment [s/he] should go to watch an all in wrestling match.”

Another wrote how despite “the rage-making crowd that may be encouraging his opponent to injure him seriously, few will dispute that as a spectacle the fights are thrilling!”

Clean wrestling celebrated the male physique in the age of Charles Atlas and keep-fit. “No other sport” wrote a female correspondent “has such fine husky specimens of manhood as wrestling. I find it such a change to see real he-men after the spineless and insipid men one meets ordinarily.”

Men too appreciated the fitness of the wrestlers who were not like other men of what one correspondent described as the “namby pamby, simpering, artificial, hair curling variety that is most prevalent in the present day’s generation”.

Interestingly, many respondents, while expressing a preference for either clean or dirty wrestling, were nevertheless regular attendees and happy to tolerate both styles, a fact perhaps explained by a letter-writer claiming that “Clean wrestling is interesting, rough stuff is exciting. If we get a bit of both it is good entertainment.” Yet, despite its suspected fakery and transgressions, All-in provided Worktowners with an entertaining evening, well-articulated by a further correspondent: “I have watched speedway, football, rugby and baseball but hats off to all the wrestlers. The excitement and joy they have, and are bringing to thousands of people in need of a tonic is certainly proof of the success. You get each week a great variety of fit athletes, something thrilling, something amazing, something that gets you excited without causing any real stampede”.

We will leave the final comment to Tom Harrisson who concluded that All-in was for one evening a way out from the dull life of routine, boredom and boss. With no press help it had become the only all-the-year-round popular sport in Worktown and over the whole country - “a new and astonishing habit”.

Next week we will be going to watch some crown green bowling matches, a more sedate sporting occasion - or was it?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here